For two years, I lived in the Himalayan foothills at a boarding school tolerated by nature. I don’t know anywhere else that has a superior combination of leopard density and wireless download speed. The wilderness was not just on our doorstep but inside our house. Spiders and scorpions the size of saucers hid in corners and behind curtains, and though I never found one in my boots, I always checked. Troops of langurs thundered across our tin roof on their way from one leafy pasture to another as we streamed the latest John Oliver exposé on our high-definition projector. We came home one day to find our house had been broken into. A bag of flour was destroyed, conveniently revealing a trail of coin-sized handprints to the window, and there was no doubt about the culprit when we realized what else was missing: the bananas. Such was life at the delicate fringe between civilization and the jungle.

That hybrid reality can perhaps best be understood through the tale of a special cat. One day, an animal-loving exchange student was out for a run with the cross country team when she saw a tiny kitten on the side of a busy road. Knowing that this fragile creature, who probably just saw its first full moon, would likely die without help, she brought it to campus and sought a warmer home for it. Put it back, some people said. Let mother nature decide what happens. But I am not a wildlife cinematographer; I am an actor in our world, and this advice felt like inaction masquerading as wisdom. This kitten had gotten lucky with who found her, and some helpers put this handful of fur in a red, plastic basket in Leaf’s hands.

Leaf and I talked about what might become of our big-eared, needle-pawed, snuggly tabby, whom we named Shera. Should we put her back in the woods? Try to find her a more permanent caretaker? We even considered raising her to adulthood and letting her go ceremoniously as if we were a wilderness rehabilitation program. We kept her and raised her and occasionally experimented with letting her be an indoor-outdoor cat (which enabled the aforementioned banana burglar). She always came back a bit disheveled, so we decided against releasing her back into the jungle. Winter came, and a network of friends organized to house her while we traveled, but summer was more difficult.

It’s worth mentioning here that the idea of an indoor cat is not a global concept. Cats have given up less than dogs in their domestication and, independent creatures that they are, weave a more opportunistic relationship with humans. In India, they generally fend for themselves, which made it hard to find veterinarians who were skilled with cats (ask me for those stories another time…). Thankfully, we found someone willing to keep Shera for the summer, but due to either a miscommunication or cross-cultural misunderstanding, she was wandering outside of the house regularly, and one day she just didn’t come back. We didn’t know for sure what happened to her, but we had a guess.

So many animal lives were cut short on the hillside. Familiar dogs became the local leopard’s latest meal. I saw a mother licking her dead puppy on the side of a road and many sick and injured animals on their last legs. These scenes broke me every time, because empathy comes from proximity. But their suffering is not their only story; the dogs that were killed by leopards lived their days roaming free along a five-kilometer loop two-thousand meters above sea level. Wealthy tourists from across North India drove up on the weekends for a glimpse of the sunrise that woke these dogs every morning. When I went for a run, they ran with me until a whiff of monkeys or another friend whisked them off in another direction. Some days I saw them on our walk home and some days I didn’t. They were their own masters — truly free. Until their last moments, they lived good lives of dignity and freedom, but their lives are delicate, and in the end, they are alone.

One day, I wandered over a hill to find one of our neighborhood dogs, an amber-coated sweetheart (in the photo above), laying down silently and acting strange. She was wagging her tail but didn’t come up to greet me. I got closer, slowly and carefully, when I realized her lower jaw was caught in a hunting trap and she couldn’t move. I called for help, and we got her out, and she was okay. She had been on the far side of a hill, out of sight of regular foot traffic. I don’t remember why I went that way that day, but if I didn’t, she may have suffered a sad and painful death. Some dogs live and die like this. Some dogs get pushed around in a stroller. This isn’t only true for dogs.

After months without seeing Shera, we assumed she was gone forever, so we printed a photo of her to put next to one of my childhood dog, Simba. We were making an ofrenda of sorts, a memorial altar to our lost loved ones. I held the small frame with teary eyes and wondered whether Shera enjoyed her freedom until her last moments. Imagining her end helped me to feel closure, and I realized I preferred the idea of her in the jaws of a yellow-throated marten to being run over by a car or falling sick and curling up somewhere safe to die slowly. To a marten, a cat is food, and that seems fair to me in a cosmic sense. It’s a less despairing, less reckless death, even if brutal.

One cool October morning, I heard meowing from the roof above our bedroom. I went outside and shouted for Leaf because I saw our cat, Shera, trying to jump down. Over three months, she had found her way home across the jungle from a crowded hill station one hour’s walk away. She spent most of the next day under our blanket on our bed, one of her favorite places. We realized later she had an elbow injury that slowed her down with a limp, but she was otherwise in pretty good condition. Just a little disheveled.

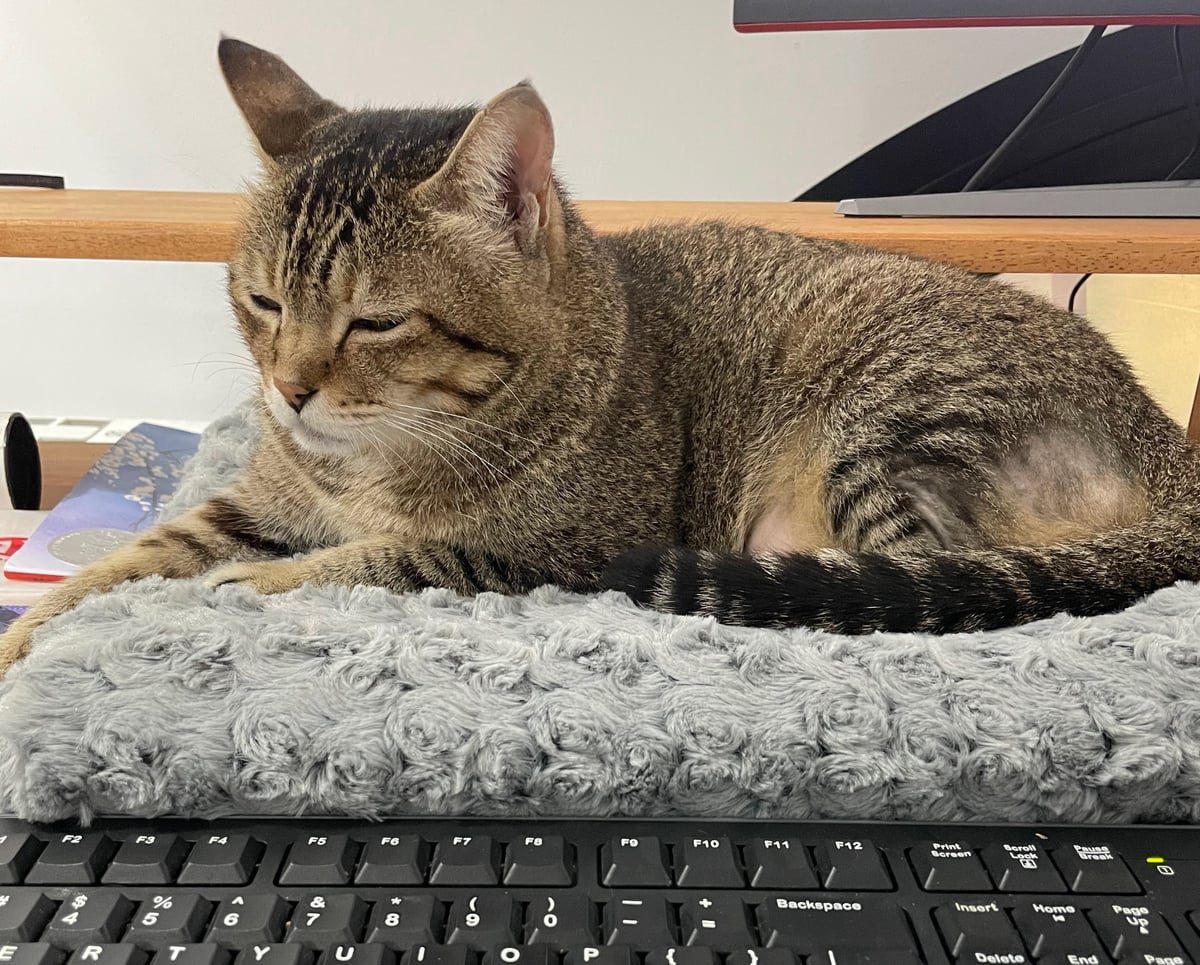

After what she had been through, we promised to do anything for this cat. We called in big favors from friends and hired a relocation agency to get her to Singapore from India during a global pandemic. She had to get spayed a second time because the first one was incomplete. In Spain now (after more paperwork), at the ripe age of 7, she has slowed down a lot and has her own cushion on my desk next to my keyboard. While I was revising this essay, Shera escaped from our backyard and went on an evening expedition. I cried when I realized that her memorial photo might need to come out again, but it turned out that she just took a nap on a neighbor’s couch. Adventures look different here.

There are no leopards in Barcelona, no dogs caught in hunting traps I might stumble upon. Much of the suffering I witness now is less tangible and comes across the internet to my screens as heartbreaking news from Gaza, Ukraine, and the US. But compared to the more isolated hillside and more neutral Singapore, I sense the world’s conflicts more strongly here. I see it on the graffiti near my home that says, ‘Tourists go home, refugees welcome.’ I hear it when the Spanish President uses the word ‘genocide’ while criticizing the Israeli government.

Looking at Shera, asleep on her little cushion on my desk, I remember that many people said to put her back in the jungle and let nature decide her fate. But I’m proud of the choice that we made to act, and I’m proud to live in a place where others are making similar choices. It’s easier to adopt a cat than to stop a war, but I don’t want to look away and let nature decide.